NOSTALGIA OF MUD

Bògòlanfini, or mud cloth, made by the Bambara people of Mali may date back as early as the 12th Century, but fashion designers have managed to keep the textile au courant by celebrating the historical cloth in a modernized way. The traditional textile was brilliantly utilized in the 80’s and 90’s by Malian fashion designer Chris Seydou, and more recently in 2007, with the ever talented Riccardo Tisci at Givenchy. Not only was the West African cloth shown on the glamorous runways of the previously mentioned designers, but it was also captured in a uniquely beautiful light in the photographs of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé. With an upcoming show entitled Africa Fashion scheduled to open in June of 2022 at The V&A, bògòlanfini will undoubtedly inspire a new crop of creative minds, sparking yet another resurrection of the now timeless textile in the fashion world.

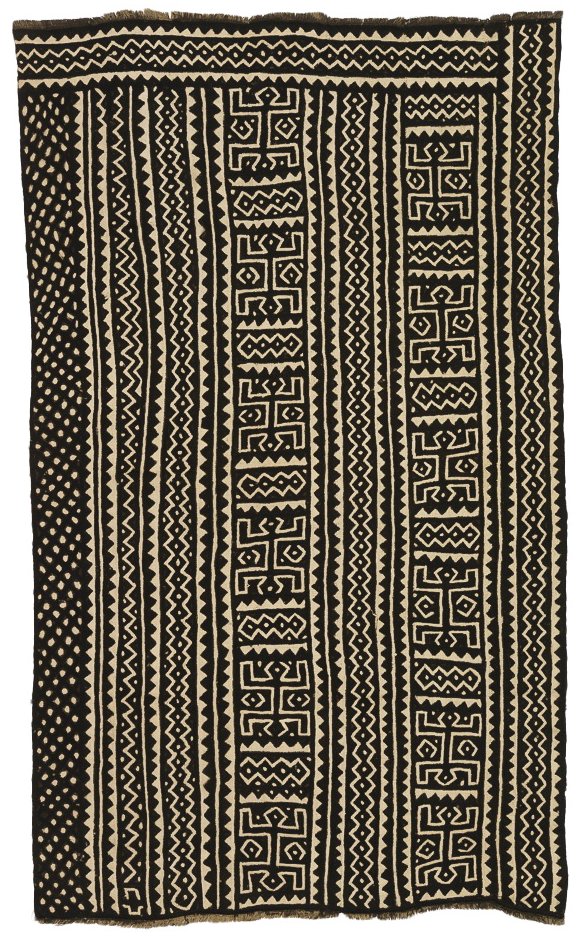

Bògòlanfini Woman’s Wrapper • Mid - 20th Century • Mali • Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York City

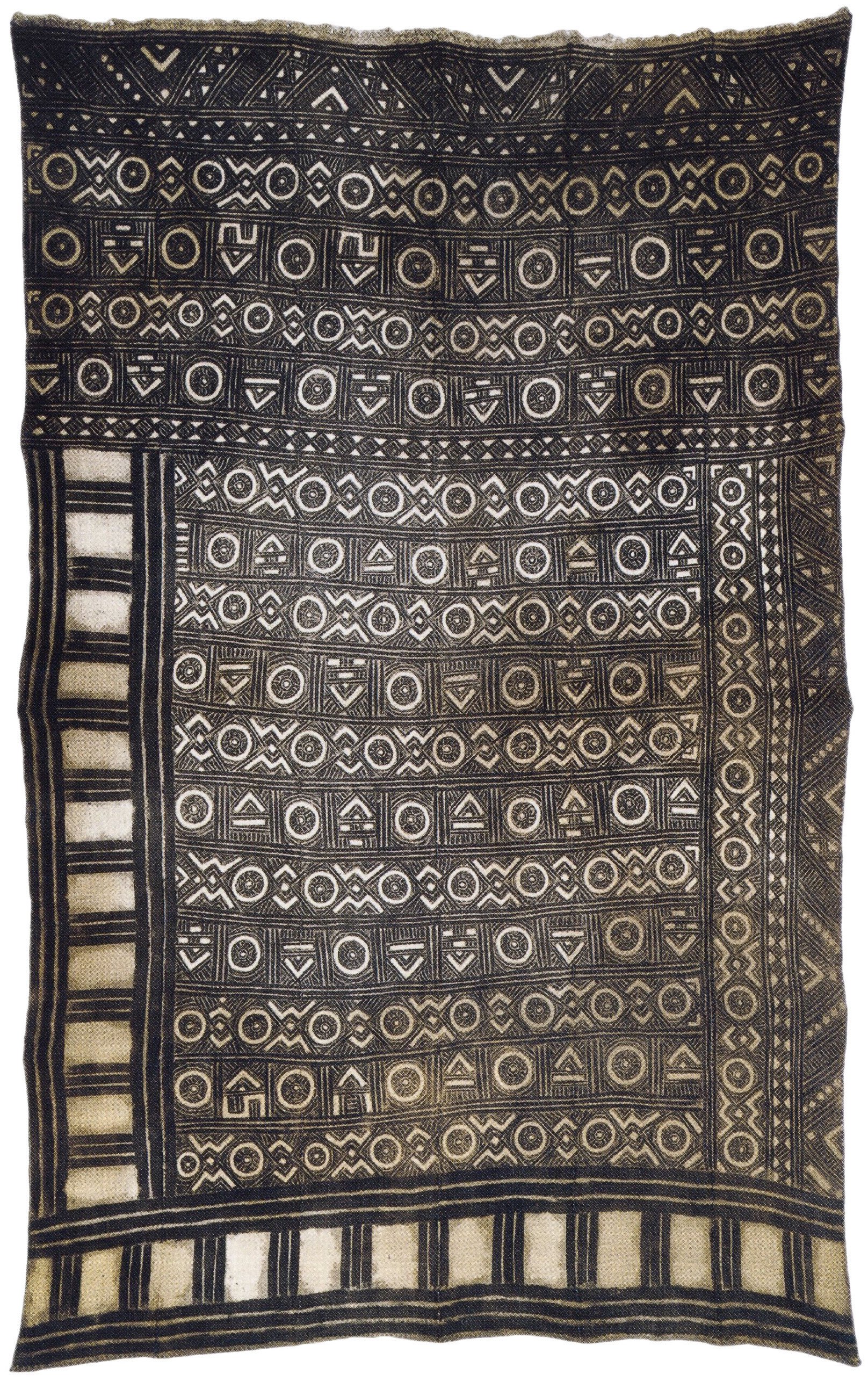

Made by the Bambara people of Mali, bògòlanfini is derived from three words in the Bambara language. ‘Bogo’ which means mud earth, ‘lan’ translates to with and ‘fini’ is cloth. Hence Mud Cloth. In traditional Malian culture, bògòlanfini is worn by hunters and serves as camouflage, ritual protection and a badge of status. The men traditionally weave the cotton cloth strips that are sewn together, thus producing the canvas that women decorate through a complex process using plant extracts and fermented mud, which is stored up to a year in a large earthen pot. In addition to their powerful graphic qualities, the numerous designs and patterns painted on the cloths denote symbolic significance

Model wearing a Chris Seydou ensemble • Nabil Zorkot • Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Most well known for his bògòlanfini, Seydou began his sartorial journey in Mali, West Africa. His work eventually transported him to the city of Abidjan in Côte d'Ivoire and then on to Paris where he worked for Yves Saint Laurent and Paco Rabanne. His eponymous label launched in 1981, applying European design techniques to traditional African printed textiles. Seydou expanded the use of bogolan through his reimagining of Western-style cropped skirts and jackets in indigenous fabrications. Seydou was mindful of the cultural context behind this rural fabric and commissioned his own materials inspired by bologan so as not to destroy any of the historical significance of existing textiles.

Bògòlanfini Tunic • 20th Century • Tenenkou Traore • Mali • Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

Vue de dos • Malick Sidibé • Image courtesy of Artsper

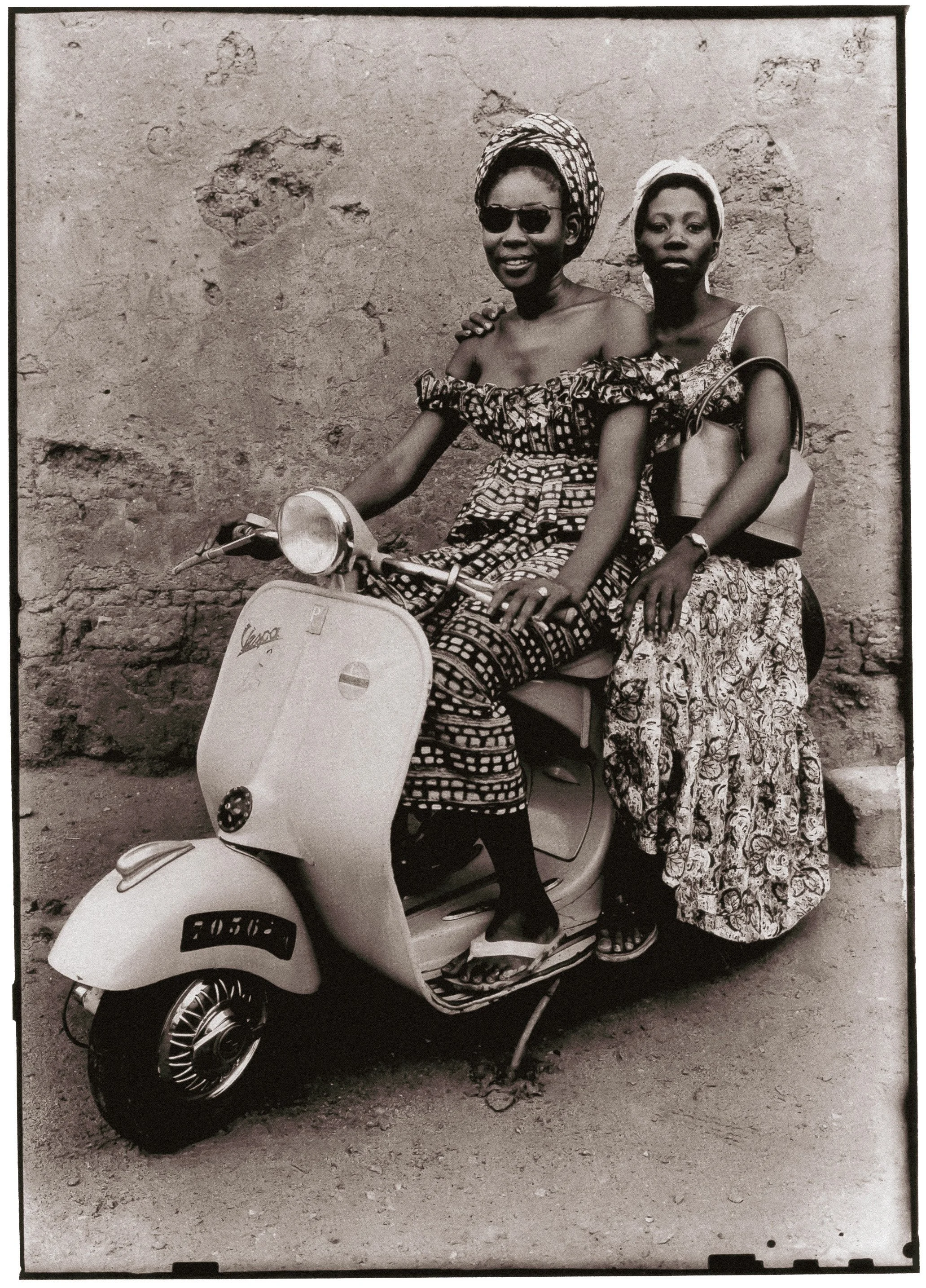

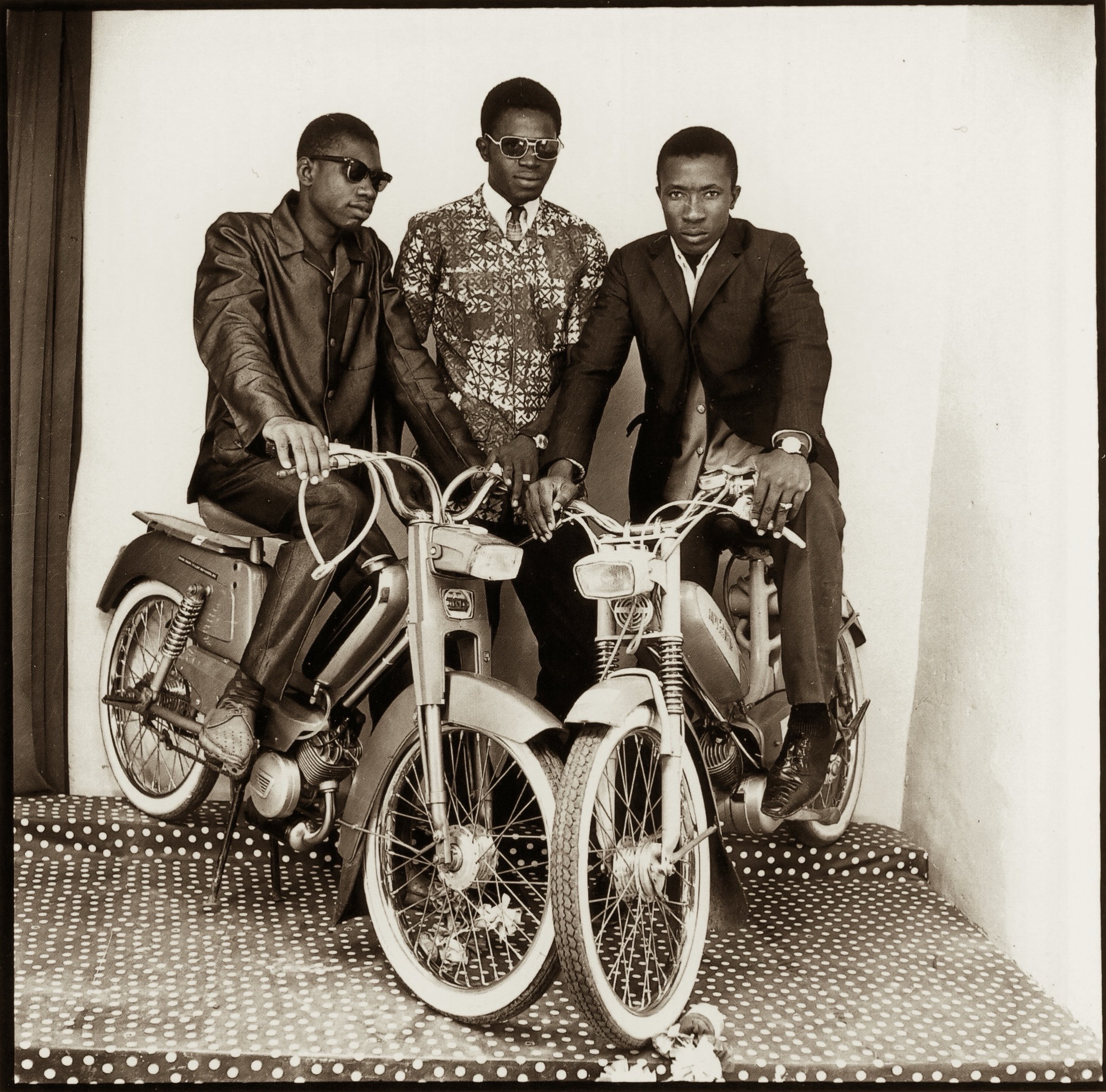

“… Out in the country, as soon as I took out my camera, everyone ran or turned away. It was believed to be very dangerous to have your photo taken because your soul was taken away, and you could die.” In 1997, Malian photographer Seydou Keïta explained to Parisian curator Andrew Magnin that photography was once rejected by African people. Not only is Keïta referring to a belief rooted in African spiritualism, but he also references the impact of colonial photography that was once used to exoticise Africa… Under colonialism, Africans were humiliatingly forced to pose for the camera as an exercise of control. Subsequently, the medium became highly distrusted. It wasn’t until photography was reclaimed by African natives themselves in the 1880s that the medium gained a sense of trust with its subjects… In the 1940s, a new wave of photographers emerged using composed portrait art to celebrate individual African identities across the continent. In Mali, it was Keïta who used photography to celebrate everyday life… Keïta was one of the first photographers to work in Mali’s capital, Bamako, followed shortly after by photographic icon Malick Sidibé – both of whom would come to define the photographic identity of 1940s-70s Mali.” • Lexi Manatakis for Dazed • All runway images courtesy of Livingly.

Vue de dos - Juin • Malick Sidibé • Image courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Untitled - Two Young Women on a Vespa • Circa 1952 • Seydou Keïta

Bògòlanfini Textile • Circa 1925 - 1950 • Mali • Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

Model wearing a Chris Seydou ensemble • Photographer Unknown

Bògòlanfini Textile • Senufo, Ivory Coast • Image courtesy of African Plural Art

Bundoo Girls, Sierra Leone • Circa 1910 • Lisk-Carew Brothers • Image courtesy of You Look Beautiful Like That : The Portrait Photographs of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé by Michelle Lamunière

Detail of a Bògòlanfini Textile

Bògòlanfini Hunter’s Tunic • Mali • Nakunté Diarra • University of Iowa Pentacrest Museums, Iowa City

Bògòlanfini Young Man’s Shirt • 20th Century • Djotene Tarawale • Mali • Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

Untitled commercial work printed by Malick Sidibé in his Bamako Studio • Image courtesy of You Look Beautiful Like That : The Portrait Photographs of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé by Michelle Lamunière

Bògòlanfini Textile • Mali • Nakunté Diarra • North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh

Bògòlanfini Young Man’s Shirt • 20th Century • Sofen Diarra • Mali • Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

Central Beledugu hunter wearing a shirt featuring the “piece of a gourd” pattern • 1978 • Kolokani, Mali • Image courtesy of The Silence of the Women : Bamana Mud Cloths by Sarah C. Brett-Smith

Bògòlanfini Woman’s Wrapper • Featuring the “carrying net” pattern • Private Collection • Image courtesy of The Silence of the Women : Bamana Mud Cloths by Sarah C. Brett-Smith

Nansun Suko and Araba Diarra wearing a post - excision retreat dress including the N’Gale wrapper • 1977 • Kolokani, Mali • Image courtesy of The Silence of the Women : Bamana Mud Cloths by Sarah C. Brett-Smith

Detail of a Bògòlanfini N’Gale Woman’s Wrapper • Circa Early 1900’s • Mali • Image courtesy of Morrissey Fabric

“Salimata Kone dyeing the half - finished N’Gale wrapper in the second dye bath made from wolo.” • 1977 • Kolokani, Mali • Image courtesy of The Silence of the Women : Bamana Mud Cloths by Sarah C. Brett-Smith

Bògòlanfini Textile • Circa 1900 - 1930 • Mali • The British Museum, London

Excised women from Metembugu • 1978 • Image courtesy of The Silence of the Women : Bamana Mud Cloths by Sarah C. Brett-Smith

Model wearing a Chris Seydou ensemble • Photographer Unknown

Bògòlanfini Woman’s Wrapper • Featuring the “tortoise’s shell” pattern • Central Beledugu • Private Collection • Image courtesy of The Silence of the Women : Bamana Mud Cloths by Sarah C. Brett-Smith

Bògòlanfini Textile • Mid - 20th Century • Mali • Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

Hunter’s Open - Sided Shirt • Featuring the “piece of a gourd” pattern • 1978 • Central Beledugu • Image courtesy of The Silence of the Women : Bamana Mud Cloths by Sarah C. Brett-Smith

Bògòlanfini Woman’s Textile • Central Beledugu • Private Collection • Image courtesy of The Silence of the Women : Bamana Mud Cloths by Sarah C. Brett-Smith

“In this photograph Salimata Kone is not applying mud dye, but bleach (sege) to a mud cloth that is almost finished” • 1977 • Kolokani, Mali • Image courtesy of The Silence of the Women : Bamana Mud Cloths by Sarah C. Brett-Smith

Detail of a Bògòlanfini Textile • Mali • Nakunté Diarra • Smithsonian National Museum of African Art

Les trois amis avec motos, studio • 1975 • Malick Sidibé • Image courtesy of You Look Beautiful Like That : The Portrait Photographs of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé by Michelle Lamunière

Vue de dos • Malick Sidibé

Portrait of Chris Seydou • Image courtesy of Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

Vue de dos - Juin • Malick Sidibé • Image courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Une pose pour moi • 1972 • Malick Sidibé • Image courtesy of Malick Sidibé Photo Poche

Bògòlanfini Textile • Mid - 20th Century • Mali • Private Collection

‘Studio Bamako’ editorial pays tribute to the late Malick Sidibé • Le Magazine Noir