CHARIOTS OF FIRE

Vintage Charioteer of Delphi Poster • Circa 1956 • Created for the Athens National Tourist Organization

Both the historic textile house of Fortuny and later, Yves Saint Laurent, found inspiration in the chiton and the peplos commonly worn in Ancient Greece. The Spanish turned Venetian designer Mariano Fortuny created his celebrated Delphos gown with his wife and muse, Henriette Negrin, in 1907. The gown, much resembling an Ionic chiton, was fittingly named in honor of the Charioteer of Delphi, the Classical Greek statue dating to 470 B.C. Monsieur Saint Laurent undoubtedly shared a similar inspiration for his Spring 1971 Haute Couture collection. Though this collection, known as La Collection du Scandale, is remembered more for its modern world references than its nod to antiquity. Despite the varied responses to each of their homages to Ancient Greece, both Fortuny and Saint Laurent were able to uniquely capture the aesthetic beauty of this magnificent era in history. As Olivier Saillard so elegantly wrote, “Couturiers and designers have always mined the past for inspiration when creating their contemporary styles and collections. History demonstrates the impossibility of resisting this temptation ; everyone gives in to it on occasion. And such research often provides a deeper understanding…”

Terracotta and black crêpe de Chine wrap worn with Hercules gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Image courtesy of Yves Saint Laurent : The Scandal Collection, 1971 by Olivier Saillard and Dominique Veillon

Hercules pleated gown with mythological figures • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • MUDE Museu do Design e da Moda, Lisbon

Also known as the Heniokhos, Greek for rein-holder, the Charioteer of Delphi is considered one of antiquity’s finest surviving bronze statues. Discovered by French excavators in 1896 during the Great Excavation of Delphi, at the Sanctuary of Apollo, the Charioteer was originally part of a larger group of statuary, including the chariot, at least four horses and possibly two grooms. Commissioned by Polyzalos, a tyrant of Gela, the Charioteer is depicted at the moment when he presents his chariot and horses to the spectators in recognition of his victory. He is cloaked in a traditional chiton or long unisex tunic which reaches down to his ankles and is held in place by a wide belt above the high waist. Two additional bands act as suspenders over the shoulders, under the arms and criss-cross at the back, which keeps the garment from billowing in the wind during a race. The defined vertical pleats in the lower part of the gown emphasize the Charioteer’s solid posture, intentionally resembling the fluting of an Ionic column, hence the term Ionic chiton.

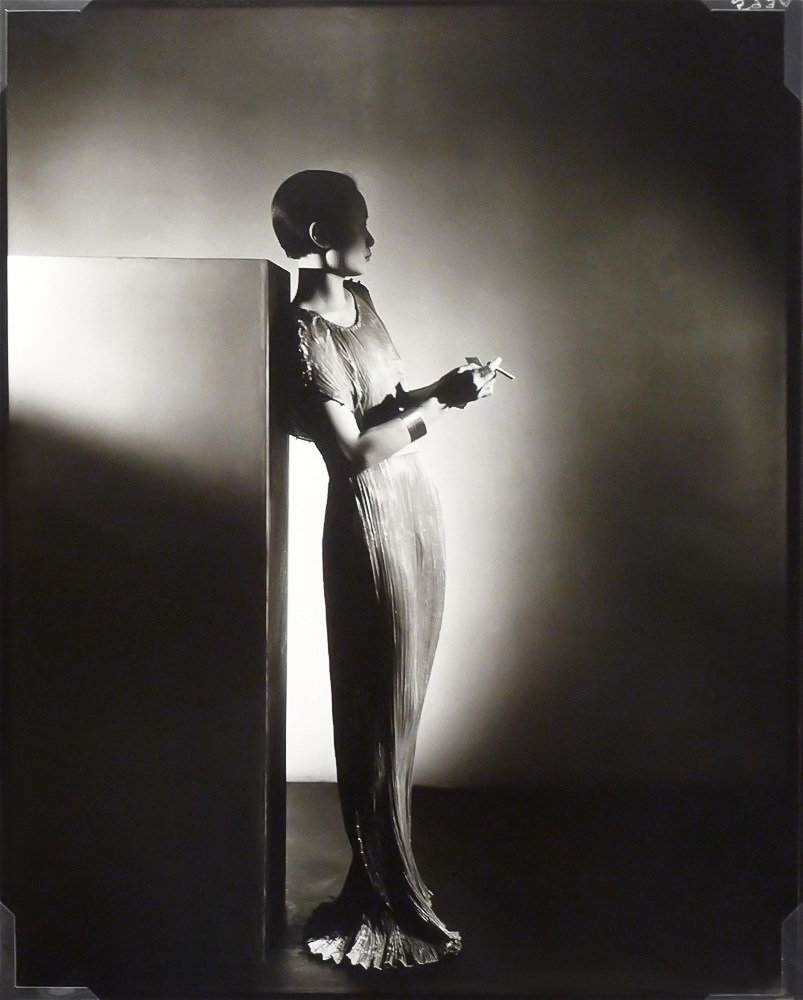

Ingmari Lamy modeling the Hercules gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Gian Paolo Barbieri • Image courtesy of Soie Pirate : The Fabric Designs of Abraham Ltd. : Volume II in association with the Swiss National Museum in Zürich

A little over a decade after the discovery of the Severe style masterpiece, Mariano Fortuny, along with the equally talented Henriette Negrin, created the Delphos gown. Shortly after, the pair designed the Peplos gown, mirroring the Peplophoros, a traditional Greek garment that was pinned at the shoulders and belted at the waist, creating straight, heavy folds to the feet. Variations of the Peplos gown, quite similar to the Delphos gown, apart from the location and drape of its waistline, can be found depicted on unearthed Greco-Roman statues displayed in museums around the world. Often adorned with Murano glass beads in various hues of silk, these Fortuny gowns became a fashion sensation worldwide, and continue to be extremely collectible with both institutions and private collectors alike. Marcel Proust, a favorite of Saint Laurent, so accurately described the Fortuny gown as “faithfully antique but markedly original."

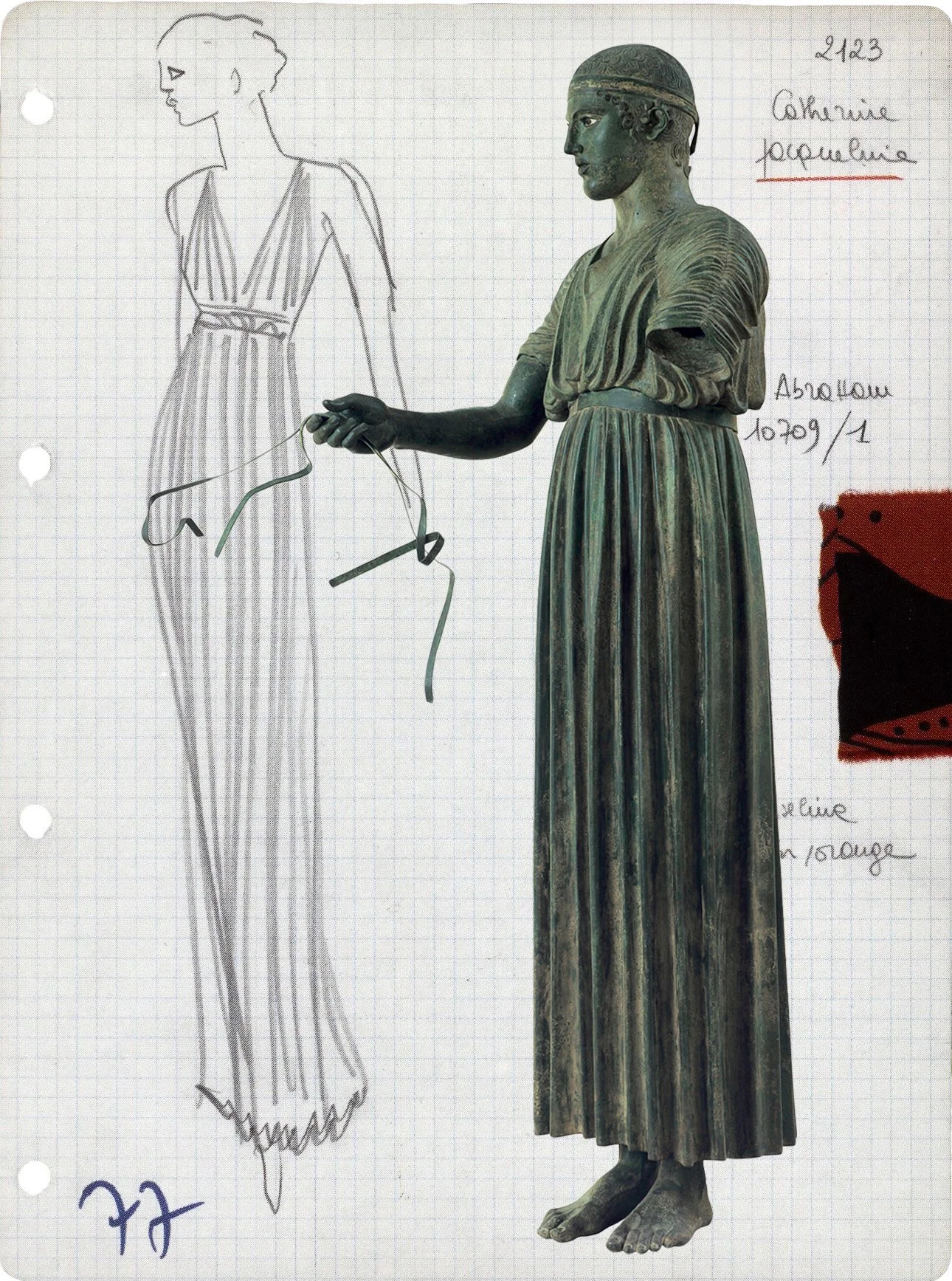

Atelier’s specification sheet for terracotta and black crêpe de Chine Hercules gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Image courtesy of Yves Saint Laurent : The Scandal Collection, 1971 by Olivier Saillard and Dominique Veillon | Collage by Sarah Aaronson

And yet again, this time nearly seventy years after the discovery of the Charioteer, long pleated gowns made waves at Yves Saint Laurent’s Spring 1971 Haute Couture presentation. “The show concluded with a group of evening dresses cut from printed fabric created by the Abraham house that reproduced motifs taken from Ancient Greek vases. For some, these designs of naked men were the ultimate insult,” wrote Suzy Menkes in her book CATWALK Yves Saint Laurent : The Complete Haute Couture Collections. Unfortunately, Saint Laurent’s renditions of the historic garment were not received with the same affection as Fortuny’s. The glamorization of the shamed war torn years in Paris referenced throughout his collection was apparently too close for comfort for the surviving generation of such a particularly dark era. “For evening wear, printed men in priapic poses encircle the dresses as they might a Greek vase. Presumably an evocation of Nazi virility?” wrote one reviewer quoted in Olivier Saillard’s book Yves Saint Laurent : The Scandal Collection, 1971. Saillard wisely continued “…that the inspiration of the past stimulates creativity, but it also creates dissonance in a discipline that is oriented toward the future.”

Lisa, Anna and Margot Duncan, dancer Isadora Duncan's adopted daughters, modeling Fortuny Delphos gowns • Circa 1920 • Albert Harlingue • Image courtesy of Mariano Fortuny : His Life and Work by Guillermo de Osma

Despite the collection’s overwhelming review by the press and Haute Couture’s old guard as brazenly distasteful, the younger generation, most famously led, in part by Paloma Picasso, the noted muse for the collection, found it to be refreshingly au courant. As Paloma Picasso and the likes of designers such as Ossie Clark, had found inspiration in the flea markets of Portobello Road, so too had Monsieur Saint Laurent found inspiration in the styles of the past, drawing equally from the Ancient Greeks and the femme fatales of the 1940s. When asked the question in an interview by Claude Berthod in March of 1971, “Why did you decide to shock with the ‘retro’ look instead of something new?” Yves Saint Laurent replied : “What can we really call ‘new’ in fashion? Whether it’s a peplum or tights, it’s all been done a hundred times before…” And yet, while the styles may be ancient, the reinterpreted designs through the eyes of Mariano Fortuny, Henriette Negrin and Yves Saint Laurent, are nothing short of brilliantly modern.

Model wearing ivy and flower belt created by Claude Lalanne, worn with terracotta and black Grecian crêpe de Chine evening gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Image courtesy of Yves Saint Laurent Accessories by Patrick Mauriès

Charioteer of Delphi • 470 B.C. • Greek • Delphi Archaeological Museum, Delphi

A Delphos gown with Murano glass beads • Mariano Fortuny & Henriette Negrin • Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney

Charioteer of Delphi, Whole, In Profile Toward Observer’s Right • 1928 • Clarence Kennedy • Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit

Mrs. William Wetmore modeling a Fortuny Delphos gown in front of a Fortuny tapestry • 1935 • Cover of Vogue • Lusha Nelson • Image courtesy of Mariano Fortuny : His Life and Work by Guillermo de Osma

Fabric sample for the Hercules gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Image courtesy of Yves Saint Laurent : The Scandal Collection, 1971 by Olivier Saillard and Dominique Veillon

A Delphos gown • Mariano Fortuny & Henriette Negrin • The Charleston Museum, Charleston

Charioteer of Delphi • 470 B.C. • Greek • Delphi Archaeological Museum, Delphi

A Delphos gown with Murano glass beads • Mariano Fortuny & Henriette Negrin • Fountainhead Museum, Fairbanks

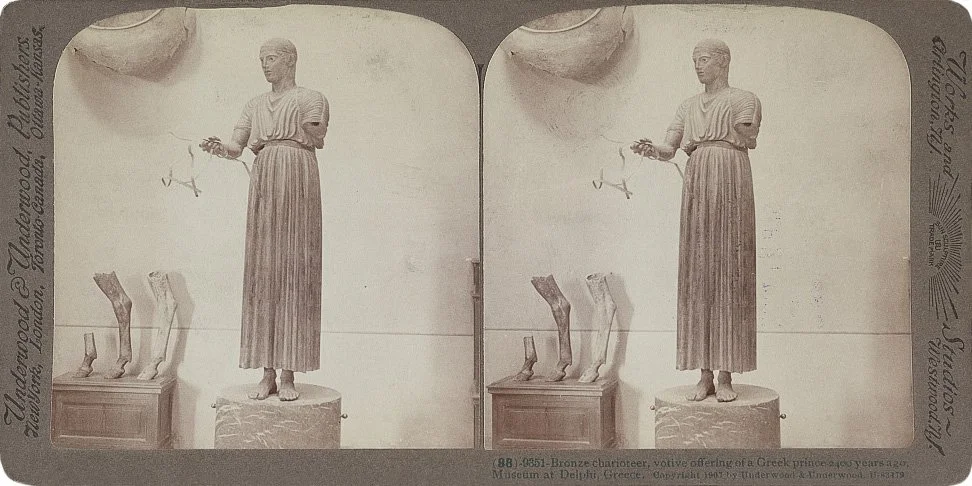

Stereograph of the Charioteer of Delphi • 1907 • Underwood & Underwood

A Delphos gown with Murano glass beads • Mariano Fortuny & Henriette Negrin • Image courtesy of Skinner Auctions

Charioteer of Delphi • 470 B.C. • Greek • Delphi Archaeological Museum, Delphi

Model wearing an early version of the Fortuny Delphos gown • 1909 • Mariano Fortuny • Fortuny Museum Archive

A Delphos gown with Murano glass beads • Mariano Fortuny & Henriette Negrin • Provenance Unknown

Elsie McNeill's showroom windows after she added Fortuny in 1928 • Image courtesy of Fortuny

Charioteer of Delphi • 470 B.C. • Greek • Delphi Archaeological Museum, Delphi

Model wearing an early version of the Fortuny Delphos gown • 1909 • Mariano Fortuny • Fortuny Museum Archive • Image courtesy of Mariano Fortuny : His Life and Work by Guillermo de Osma

A Delphos gown with Murano glass beads • Circa 1913 • Mariano Fortuny & Henriette Negrin • Palais Galliera, Paris

Mai-Mai Sze modeling a Fortuny Delphos gown • Circa 1934 • George Platt Lynes

Charioteer of Delphi, The Lower Portion of His Barment and His Feet, Facing • 1928 • Clarence Kennedy • Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit

A Peplos gown with Murano glass beads • Circa 1910 • Mariano Fortuny & Henriette Negrin • National Museums, Scotland

Model wearing a Fortuny Peplos gown • Mariano Fortuny • Fortuny Museum Archive

From left to right: Terracotta Figure of a Woman • Mid-5th Century B.C. • Greek • The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City | Statue of a Woman Wearing a Peplos (Peplophoros) • 1st Century B.C. - 1st Century A.D. • Roman • Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton | Marble Statue of Eirene (The Personification of Peace) • Circa 14-68 A.D. • Roman Copy of a Greek Original by Kephisodotos • The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Charioteer of Delphi, Whole, Back • 1928 • Clarence Kennedy • Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit

Original sketch for terracotta and black Grecian crêpe de Chine evening gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Image courtesy of Yves Saint Laurent : The Scandal Collection, 1971 by Olivier Saillard and Dominique Veillon

Stereograph of the Charioteer of Delphi • 1907 • Underwood & Underwood

Peplophoros (Main View, Front) • 25 B.C. - 125 A.D. • Roman Copy of a Greek Original • The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Los Angeles

Clarisse Coudert, wife of publishing magnate Condé Nast, modeling a Fortuny Delphos gown • Circa 1917

Grecian wedding gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Image courtesy of Yves Saint Laurent : The Scandal Collection, 1971 by Olivier Saillard and Dominique Veillon

Elsa Faúndez-Dodero modeling the Grecian wedding gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture • Yves Saint Laurent • Image courtesy of Yves Saint Laurent : The Scandal Collection, 1971 by Olivier Saillard and Dominique Veillon

Charioteer of Delphi, Head Turned Two-thirds Toward Observer's Right • 1928 • Clarence Kennedy • Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit

From left to right: Peplophoros • 1st Century B.C.E • Roman • Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara | Woman “Peplophoros” • 1st Century B.C.E • Greek • The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore | Torso of a Peplophorus • 450-300 B.C. • Roman

Cardboard mannequin cutouts cloaked in Fortuny • 1911 • The ‘Salon Fortuny’ at the Exposition des Travaux de la Femme, Paris

The Delphos gown • Circa 1910 • Mariano Fortuny

Model wearing Grecian crêpe de Chine evening gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Sophie Carre • Image courtesy of Fondation Pierre Bergé - Yves Saint Laurent, Paris

Blue and black Grecian crêpe de Chine evening gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Image courtesy of Yves Saint Laurent : The Scandal Collection, 1971 by Olivier Saillard and Dominique Veillon

Model wearing blue and black Grecian crêpe de Chine evening gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Image courtesy of CATWALK Yves Saint Laurent : The Complete Haute Couture Collections by Suzy Menkes

Printed Silk Crêpe De Chine • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent in collaboration with Abraham Ltd. • Image courtesy of Soie Pirate : The Fabric Designs of Abraham Ltd. : Volume II in association with the Swiss National Museum in Zürich

Atelier’s specification sheet for blue and black Grecian crêpe de Chine evening gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Image courtesy of Yves Saint Laurent : The Scandal Collection, 1971 by Olivier Saillard and Dominique Veillon

Model wearing blue and black Grecian crêpe de Chine evening gown • Spring / Summer 1971 Haute Couture Collection • Yves Saint Laurent • Image courtesy of Yves Saint Laurent : The Scandal Collection, 1971 by Olivier Saillard and Dominique Veillon